Last year, I was exposed to experimental artist Carolee Schneemann’s work in a class focused on sex as an artistic subject of the 60s and 70s. Her visual expression of blatant sexuality was so intriguing that I wanted to share a few examples of her work while discussing the controversial debate over whether her ideas fit into the feminist framework at all.

One of her most famous works is an experimental film depicting Schneeman herself and her partner at the time, James Tenney, having sex. Entitled Fuses (1967) to represent the metaphorical blending of bodies into one in the act of love-making, Schneemann’s work not only attempts to destroy sexual taboos but emphasizes the validity and importance of female autonomy and pleasure in a male world.

In an interview with Kate Haug from her book Imaging Her Erotics, Schneemann addresses the backlash she received for her work. Men seemed to have more positive things to say about the film than women of the time, which is both surprising to me and completely sensical. Given that the narrative of female sexuality was always posited in relation to her male counterpart, existing for him and not her, many women received the film poorly and claimed that her work was simply “narcissistic exhibitionism.” However, on the other hand, the film empowered some women who have never been shown active depictions of female bodies or genitalia as opposed to an experience of passive reception or victimization.

Yet generally, the feminist intentions of the piece were overlooked and deemed counter-intuitive because Schneemann was inadvertently feeding into the male fantasy with borderline pornographic material and demonstration of “the overt penis as a source of active pleasure,” explaining the more positive responses of her male audiences.

Keeping in line with accusations of her work being mere “narcissistic exhibitionism,” Interior Scroll (1975) is another of Schneemann’s most problematic creations. Schneemann herself is again the focus of the work, this time a performance piece where she removes a long scroll of paper from her vagina on stage and recites its written contents. In its first performance, the scroll is printed with a poem from her book Cezanne, She Was a Great Painter. This work is widely empowering—a frustrated listing of the misogynistic ideals Schneemann that has fought with and a warning of sorts for women everywhere: always be prepared for others to make femininity both an enemy and a useful commodity. In the next scroll, Schneemann has printed a conversation between her and a male filmmaker. It seems to exemplify the sexist criticisms Schneemann that received from him, disguised as constructive criticism or simple rejection of her general art form or her ability to do things in the “correct” way.

Centrally, however, the work is focused on the vagina as a powerful entity deserving of great admiration and recognition of its value. As recounted in a celebratory journalism piece remembering her work, Schneeman’s goal was to “physicalize the invisible, marginalized, and deeply suppressed history of the vulva, the powerful source of orgasmic pleasure, of birth, of transformation, of menstruation, of maternity, to show that it is not a dead, invisible place.”

While Schneemann’s work presents to the viewer a view of female sexuality we are rarely exposed to, her work opens up discussion about sexuality’s place in the feminist movement. It seems also quite relevant to the culture of today, where hypersexuality in young girls seems to be increasing due to the influence of social media. Not only are they often too immature to be expressing themselves in this way safely, user content on apps like TikTok reinforce the idea that girls’ sexualities are something to be expressed solely for the consumption and satisfaction of others. Schneemann’s work is so important because it highlights female sexuality as a strong individual power, something that ought to empower a woman rather than place her in subordinate positions to those who do not value her. That being said, the hope is that with more messages urging women to take full ownership of their bodies and sexual expression, we can reverse some of the harmful ideas taking hold of young girls everywhere.

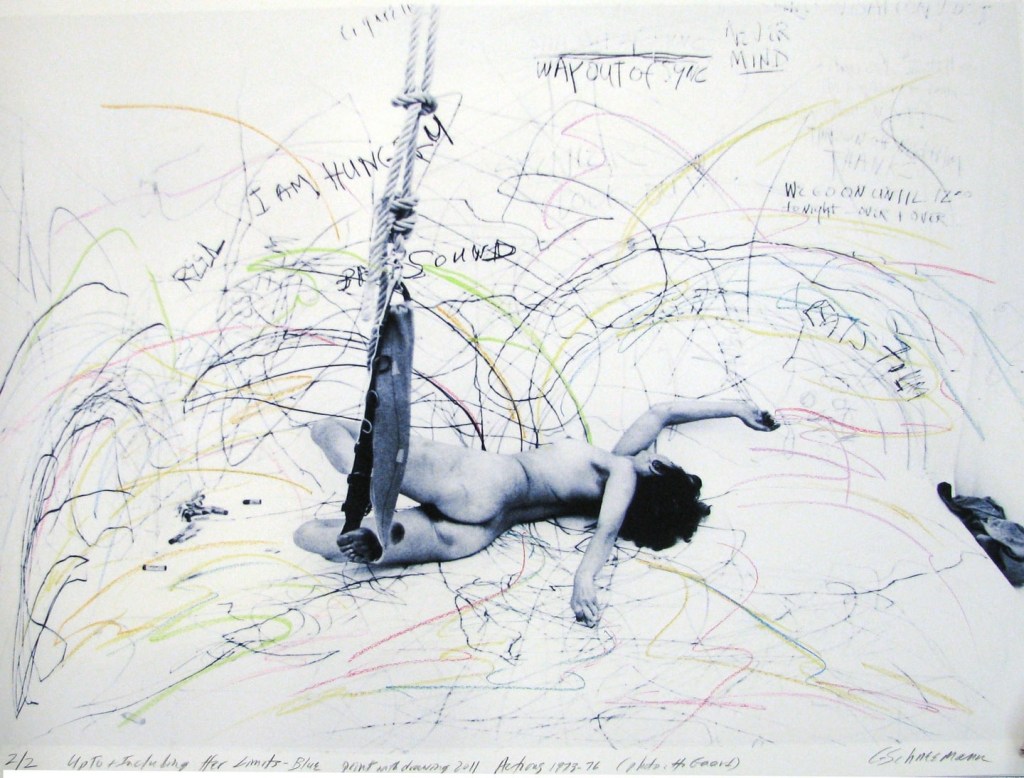

Illustration: Up to and Including Her Limits (1973–76), Copyright © 2021 Hales Gallery

Leave a comment